Antiguan artist and writer Frank Walter was an eccentric recluse who is now being celebrated as one of the Caribbean’s most complex and prolific artists of color.

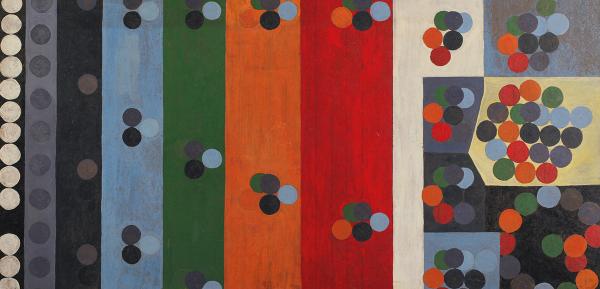

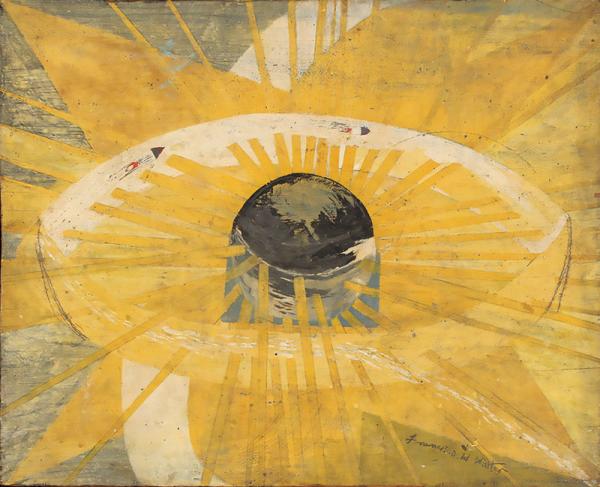

Walter produced paintings that dealt with nature and social identity as well as abstract explorations of nuclear energy and the universe. His portraits were both real and imagined –including a ballerina’s legs in African Genealogy, Hitler in Dipsomaniac, Walter himself as Christ on the Cross, and Prince Charles and Princess Diana as Adam and Eve.

Walter’s miniature landscapes of Scotland, the country that he fell in love with during a visit in the 1960s, show remarkable attention to detail in capturing the genius loci of the many places he called home, sometimes for less than twenty-four hours. As with his Antiguan vignettes, he transports the viewer through his direct, unadulterated approach. Typically painting in oil on rudimentary materials, his work reveals a heightened awareness of place and a unique, immediate vernacular style.

Besides painting, sculpture, and photography, Walter also created poetry, plays, and music. He penned over twenty-five thousand pages of essays on art, history, and genealogy; a seven-thousand-page typewritten autobiography, and a privately printed book entitled Sons of Vernon Hill. Over 400 hours of tape recordings reveal a philosopher whose voice sounds not unlike Winston Churchill’s and resonates deeply with rich intellectual inventiveness and compassion.

Self-styled as the 7th Prince of the West Indies, Lord of Follies and the Ding-a-Ding Nook, Walter was an artist with acute philosophical sensibilities, intellectual genius, and along with those attributes, perceived mental imbalances. He struggled with society’s inequality, with race proving to be one of the most difficult issues for him.

This stemmed from the then-forbidden secret handed down to him from family matriarchs – namely, that he was descended from both slave

owners and the enslaved. As a result of this knowledge, which was taboo for his time, and his exposure to harsh racism in the United Kingdom, Walter entertained delusions of aristocratic grandeur, chiefly the belief that the white slave owners in his family linked him to the noble houses of Britain and Europe.

Noted as the first person of color to manage an Antiguan sugar plantation, Walter was offered a lucrative position to manage the entire Antiguan Sugar Syndicate. He opted instead for a working tour of industrial Europe and Britain, aiming to study new technology

abroad to bring back to his country. England, however, was nothing like his island paradise, and racial prejudice made it impossible for him to secure the kind of managerial position his skills deserved.

Added to this disappointment, he found himself distanced from family members who could pass for white. Racial clashes in London further isolated him – until, suffering from hallucinations, Walter was institutionalized.

Walter was perpetually trapped between the worlds of Otium and Negotium and was isolated by his acute intelligence. Returning nearly eight years later to an economically troubled Antigua, Walter relocated to Dominica to carve out of the forest, by hand, his agricultural estate Mount Olympus, only to

have it confiscated by the government after many years of toil. Despondent, he returned to Antigua where he retreated from society after a failed campaign for prime minister.

Art became his solace, as he returned to nature, high on a hillside without running water or electricity to spend the last decades of his life in peaceful isolation. Walter created his own universe to insulate himself and others from injustice, and this book celebrates his achievement. Walter died in 2009, a visionary and, without question, the most enigmatic Caribbean artist of his time.