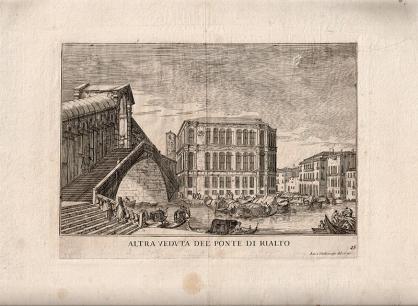

Rialto is the island of the legendary birth of Venice: people from the mainland are said to have settled here in the ninth century; convenient landing points facilitated the development of a commercial centre.

In the twelfth century, Doge Enrico Dandolo referred to it as Rivoaltinum forum; in 1442, Florentine merchant Jacopo d'Albizzotto Guidi was amazed at its many activities; in 1496, Vittore Carpaccio illustrated its wealth, alluding to its cosmopolitanism; the following year, the Council of Ten stated that it should be seen as a ‘shrine’, while historian Marin Sanudo described it as ‘the richest part of the world’. In The Merchant of Venice Shakespeare has Solanio say to Salerio ‘What news on the Rialto?’.

In modern times, therefore, the heart of the city was Rialto!

Rialto over the centuries

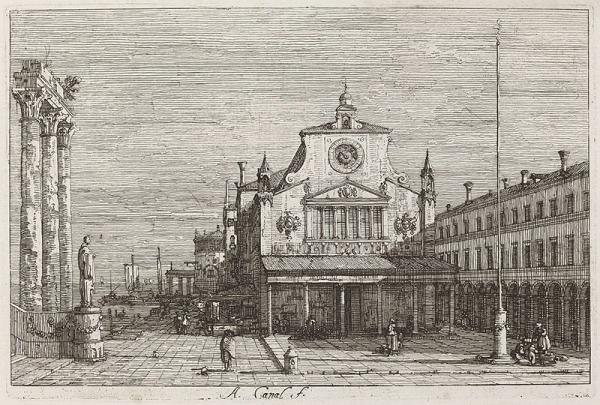

The ancestor of the stock exchanges, the centre of international high finance. In the sixteenth century, news concerning prices and international conflicts would arrive at Rialto. The physically precarious exchange counters were just like the modest wooden board painted by Carpaccio in a picture for the Scuola Dalmata. Next to Saint Matthew, protector of bankers, cash was ‘proof’ of the solidity of the noble owners. The site, frequented by merchants from all over the world, was the very heart of the Serenissima's high finance and of its relations with India, China, Persia...

The ancestor of the stock exchanges, the centre of international high finance. In the sixteenth century, news concerning prices and international conflicts would arrive at Rialto. The physically precarious exchange counters were just like the modest wooden board painted by Carpaccio in a picture for the Scuola Dalmata. Next to Saint Matthew, protector of bankers, cash was ‘proof’ of the solidity of the noble owners. The site, frequented by merchants from all over the world, was the very heart of the Serenissima's high finance and of its relations with India, China, Persia...

Silks, gold and precious jewellery. Descending from the wooden bridge, the lane of the Oresi (goldsmiths) was marked by the long double building that also housed the Drapery. Fabrics and silks, but above all jewellery, gold, silver: the building is the result of the sixteenth-century rebuilding of the entire Campo di San Giacomo after the terrible fire that struck the whole island in 1514. The square has uniformly shaped porticoes, some of which are frescoed.

Herbs, cheese, meat, fine fish. All around, along the convex side of the Grand Canal, there was the Erbaria and then shops selling ropes, cheese, beef or horsemeat, poultry and further on, fish of all shapes and sizes. In turn, these stalls were followed by insurers and notaries.  On the stalls selling fruit and vegetable from Sant'Erasmo, from other islands in the lagoon or from the Treviso area, one could find (and still can) bruscandoli (wild hops), salicornia, asparagus, castraure (the first shoots of the violet artichoke grown in the lagoon). Boats laden with herbs, barrels of wine, or sacks of coal would moor along the banks of the Grand Canal.

On the stalls selling fruit and vegetable from Sant'Erasmo, from other islands in the lagoon or from the Treviso area, one could find (and still can) bruscandoli (wild hops), salicornia, asparagus, castraure (the first shoots of the violet artichoke grown in the lagoon). Boats laden with herbs, barrels of wine, or sacks of coal would moor along the banks of the Grand Canal.

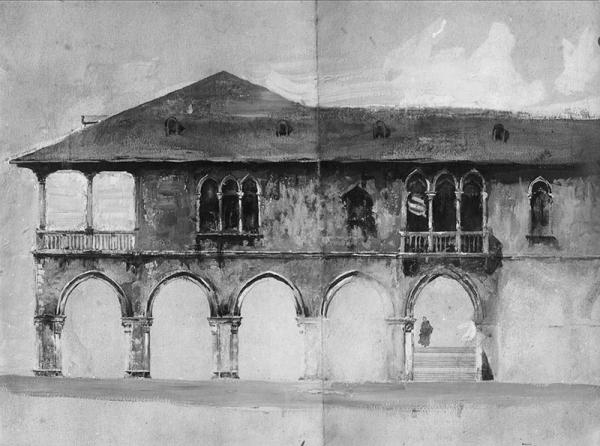

Jacopo Sansovino's Fabbriche Nuove (the Courts). This is a long (88 metres) three-storey building that runs along the northern bank of the Grand Canal, built between 1550 and 1556 by Jacopo Sansovino, who had been commissioned by the Council of Ten to complete the reconstruction of the market and to ‘tidy the area’ by making the view from the water more decorous.

With great astuteness with regard to the urban functions and of the water and pedestrian access, the slightly curved building follows the shoreline and facilitates the unloading of goods. On the ground floor, in front of the shops (now closed) and warehouses, a portico overlooks the canal.  On the upper floors it is occupied by the offices of the Court, now being transferred to Piazzale Roma, with the result that the building, owned by the State, is destined for a change of use.

On the upper floors it is occupied by the offices of the Court, now being transferred to Piazzale Roma, with the result that the building, owned by the State, is destined for a change of use.

The Pescheria (fish market) is a neo-Gothic building owned by the municipality and built by Cesare Laurenti and Domenico Rupolo in 1907. On the ground floor, an open loggia with three naves is characterised by singularly imaginative capitals with fish, heads of aquatic animals, sea monsters fresh sardines, monkfish, giltheads, sea bass, cuttlefish, eels, schie, canoce (shellfish) and crustaceans: the range of seafood on sale is still very wide.

The first floor (almost 1,000 square metres), accessible by an external side staircase, has been empty for about ten years. Enclosed on three sides by two and three-light windows, with a small loggia overlooking the Grand Canal, it is full only of pigeon guano.

More cultural functions (temporary exhibitions, cooking classes, debates, book presentations) could coexist with the fish market beneath.

More cultural functions (temporary exhibitions, cooking classes, debates, book presentations) could coexist with the fish market beneath.

In the future? Today, the ensemble of canal banks, little squares, passageways and market buildings are not a traditional tourist destination. Most guidebooks only mention the Rialto bridge and the small church of San Giacomo as 'monuments', as emblems of the city's distant origins.

However, even in recent years, for a couple of hours, both the bridge and the whole area are so crowded that it is difficult to pass by: citizens with shopping bags pass by tourists attracted by low-quality souvenirs.

However, you can still meet the few holders of a ‘mercantile’ know-how and of an artisan culture handed down through generations. A stroll around the island, through the calli and by the minor buildings reveals the extraordinary richness and complexity of the lagoon city and its thousand-year history. Yet Rialto is also a neglected area, left to decay and marked by the impoverishment of certain areas, as well as suffering the difficulties often experienced by traditional markets in historic cities overrun by tourism.

In Venice, as in other European centres, the decrease in the resident population, but even more so the emergence of a large number of small supermarkets – in which the range of everyday products is fairly wide and opening hours extend well into the evening – compete with the market. Of course, places change because the habits of their inhabitants change.

In Venice, as in other European centres, the decrease in the resident population, but even more so the emergence of a large number of small supermarkets – in which the range of everyday products is fairly wide and opening hours extend well into the evening – compete with the market. Of course, places change because the habits of their inhabitants change.

‘Venezia xe un pesse e Rialto ‘l so cor’, says a popular song written by Andrea Vio, owner of a stall in the Pescheria with a group called Ground Zero. The fact that it is also one of the Venetians' best-loved places is demonstrated by the signs that have appeared on the stalls and the more than five thousand signatures calling for its preservation.

The recent pandemic has led to the rediscovery of ‘neighbourhood' shops, which are much appreciated in Italian and European historic centres. Today, rethinking the role of a market that has a thousand years of history and reintroducing some of its functions means thinking about the future. However, it is necessary to re-invent the use of the spaces with a coexistence of outlets, catering, craft and cultural activities that trigger some mutual interest. Just as is happening in Barcelona, London, Bologna and Florence, in Venice those who buy fish or herbs from the lagoon could be attracted by the simultaneous offer of exotic products, new glass or paper artefacts, a temporary exhibition on the history of the city, a cookery school or the presentation of a book. There are public buildings in Rialto that are empty or about to be emptied: they could be used for workshops, training courses, innovative projects for students, researchers, Venetian and foreign artists.

Relaunching a historic market requires overall urban strategies, not based exclusively on a tourist monoculture, but capable of proposing work compatible with the fragility of the whole. Aimed primarily at residents, they could provide quality services and experiences for the many visitors to take home with them. Enhancing the area's excellence could be a way for the future city to exist and maintain its beauty, and indeed to make it the object of specialist training and the transmission of knowledge; ultimately attracting new citizens.

***

To find out more:

progettorialto.org

Donatella Calabi, Ludovica Galeazzo (ed.), Acqua e cibo a Venezia. Storie della laguna e della città, Venice, Marsilio 2015

Donatella Calabi, Rialto. L’isola del mercato a Venezia. Una passeggiata tra arte e storia, Verona, Cierre 2020

Venezia è viva, Paris, Liana Levi 2021

***

Donatella Calabi, professor of History of cities at the IUAV University of Venice, has also lectured at MIT, Harvard and EHESS in Paris. She has published in English, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, Dutch, Hebrew and Japanese. Concerning Venice, she has written Acqua e cibo (Marsilio 2015), Ghetto (Bollati Boringhieri, 2016) and Rialto (Cierre 2020).